NYANSAPO and the fight for space, place and „race“ in France.

By Tonica Hunter

Je demande l'interdiction de ce festival. Je vais saisir le Préfet de Police en ce sens.

— Anne Hidalgo (@Anne_Hidalgo) 28. Mai 2017

It was the festival which Anne Hidalgo, the Mayor of Paris, almost banned, denouncing it as „prohibited to white people“. NYANSAPO was the first edition of a planned series of festivals organised by black wom*n based in France but with links to various feminist activists and artists of the African Diaspora across Europe.

The name of the festival itself „NYANSAPO“ derives from West African (namely Ghana and Ivory Coast) symbols called „Adinkra“. This symbol stands for wisdom and discerning one’s way to realise one’s goals through experience and practical measures; a seemingly positive and harmless proposition for any activist movement for social change.

wom*n

The term wom*n is often used to promote inclusivity among cis- and transgender women. It avoids the suffix "-men" or "-man" in an attempt to break away from patriarchal linguistic norms which disregard the existence of trans/intersex individuals.

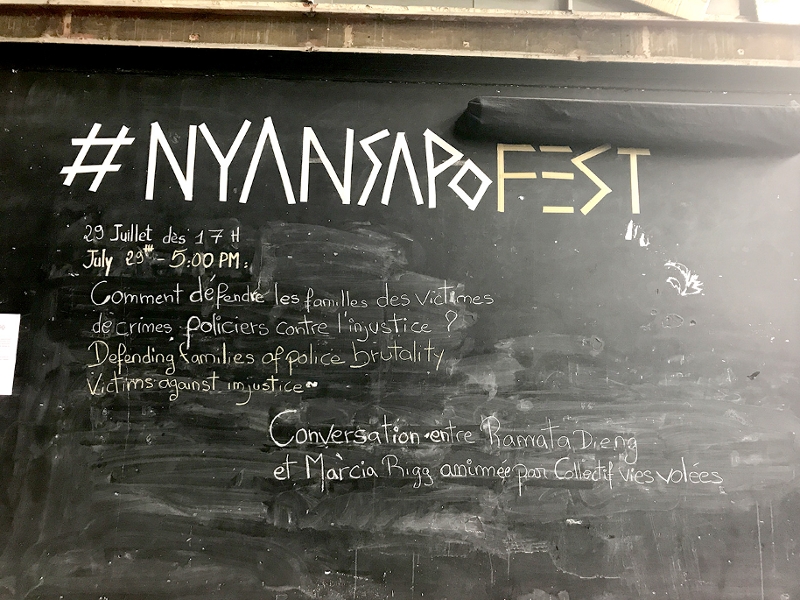

The three day festival offered a packed programme of workshops, round table discussions, performances, exhibitions and lectures. Its programme was carefully curated to include a range of topics: from colourism to „hair as a political tool“ to police brutality; creating transnational links of solidarity between activist groups as well as highlighting specific plights and voices of refugees and migrants.

The aim of the NYANSAPO festival was to bring together afrofeminist individuals and collectives fighting to put an end to racial violence and the colonialist, patriarchal and capitalist structures which promote such violence. Described by the organisers themselves (the Mwasi Collective) as a „festival afroféministe militant“ the image invoked was one of a young, feminist movement à la black panther and the reactions to this were divided.

The Backlash

The outrage came from the fact that the organisers had divided the programme (published in mid-May) as follows: a space for black wom*n only (80% of the activities) on strategies, group work and reflection on afro-feminist theory and self-care and a separate part of the programme for black people (all genders) only on the black community and struggles of people of African descent. Spaces were also allocated for wom*n of any ethnic minority; and finally there were parts of the programme open to all - including round table discussions, shows and exhibitions.

Critique quickly spread on social media sites of anti-racism organisations across France which followed suit to Hidalgo’s stance. The International League Against Racism and Antisemitism (LICRA) claimed Rosa Parks herself would „turn in her grave“ at the idea. Twitter accounts of key opinion holders in France labelled the organisers „racist anti-racists“ with the French philosopher Raphael Enthoven denouncing the festival as suggesting all white people to be racist due to its „exclusive“ programme.

Given the increasing popularity of the Front National in the French elections in May polls earlier this year, Enthoven even went as far as to say that initiatives such NYANSAPO festival gave the FN reason to exist.

Inevitably, all of this made the festival and its programme even more visible.

The organisers retorted with a statement which claimed the attacks on the festival were simple propaganda aimed to derail their purpose and lead to the demise of the festival. Despite the pressure, the festival activities were not changed: the show would go on and, embarrassingly, Hidalgo had to retract her statement.

The festival activities which were open to all were to be located in la Générale located in the 11e arrondissement of Paris and funded by the mayor of Paris’ office - but the workshops for wom*n of colour and black wom*n only were located in private spaces. Problem solved? Not quite. The issue for its critics, was this very division of space and how and to whom it was allocated.

To understand why, it’s important to consider the geographic (national and local) specificities in which the NYANSAPO took place. France is a country where the acknowledgment of visible „difference“ is notoriously polemic. It is a Republic renowned for its application of Laïcité - (secularism/laicism) i.e the separation of the State and religion which dates back to 1871; a principle of which is it openly proud and upholds in the name of equality amongst all (wo)men.

This is allegedly as opposed to acknowledging difference and creating division. As such, French secularism is often described as an antithesis to the British „multicultural“ approach which promotes equality by recognising cultural, ethnic and religious diversity.

Despite the aim of laicism in principle, its practice is somewhat contradictory. In a State where, as a result of such ideology, wearing the burqa is banned and in a city such as Paris with a history of urban rioting (most famously in 2005), the consequences of laïcité have proven somewhat ostracising and divisive.

The locality of Paris is significant given the history of its „banlieues“ (suburbs) where predominantly ethnicities from Sub Saharan and/or former French colonies including the Maghreb reside. On top of this, there are accounts of deaths of young ethnic minorities in cases of police brutality (which have led to urban riots in the past) and cases of racial profiling, not to mention Islamophobia.

Given this complex merger of social issues and tensions, the secularist approach could be said to have negatively affected those very persons it purports to protect. What’s more, even taking statistics denoting ethnic minority groups is not a legal act - national census actually avoids this entirely.

How can approaches to addressing these populations then be targeted and take the specificity needs into serious consideration? Space, „race“ and place (socio-economic, class for example) become entwined, sensitive therefore in the context of such a festival such as NYANSAPO - which highlighted all three explicitly.

Tonica Hunter

Bad&Boujee in Paris

Along with the Bad&Boujee (the all black, all female collective founded in 2017) collective from Vienna, I was invited to perform at the opening of the NYANSAPO festival.

We distinctly discussed our presence there beforehand and our safety: not only were high tensions with heavy attention on the festival but also we discussed having to pre-empt a police presence and protests perhaps.

After a sound check that afternoon, we arrived at the venue on 28th July in the evening at the time of a round table discussion on exploitation of wom*n in manual work. The opening was well attended and the energy was very positive and we moved around the room, finally putting faces to the names of the organisers who invited us and greeted various other attendees and artists.

There was a clear buzz and excitement around the festival finally taking place, with people networking, seeing familiar faces from afrofeminist collectives from Lyon, Brussels and the UK Black Lives Matter team to name a few. This alone demonstrated the high level of attendance and content of the discussions were off to a very good start. There was no tension, no animosity, no challenge to the festival layout - it was well received and clearly well planned.

The visible „division“ of the programme came at the point of registering for workshops which were designated as per ethnicity/gender. Once registered, a subsequent „secret“ location for the workshops were sent by email to those who had signed up beforehand.

What became clear over the course of the two days of workshops was the need for these spaces. In the same way wom*n who have been physically/sexually assaulted may need spaces where they can speak out on their experience, without judgement and without retort and defensiveness from an opposing view. Such spaces for black women should surely not cause such disdain or shock.

„I feel the festival was successful“

A few days after the event I caught up with Farah Medarbi, one of the members of Mwasi collective. She commented almost straight away on the absence of other groups, mainly white people, and the fact this was not a group that was present at all. „We [black wom*en] were here, we were not afraid; and to this end, I feel the festival was successful“, she asserted. She alluded to the fact that other ethnicities might have felt threatened by the festival and its dedicated workshops but that these spaces were full of interesting people and points of view so, effectively, the critics and sceptics missed out on something. As a result of the festival, many people, Farah told me, had expressed interest to sign up to join the collective which is in fact more broadly open to wom*n of „African descent“.

The lesson here seems to be that critique from afar is problematic: the presence of those who were sceptical about the festival’s purpose could have been key in addressing such topics in an open forum and coming to an informed discussion. If, such groups who were against the festival spoke against its exclusivity, then why not come, express interest, be attentive and listen, as well as express an alternative point of view?

In any case, what the NYANSAPO festival clearly achieved was having created an important, necessary, safe space for discussions on sensitive topics for significantly marginalised groups.

Publiziert am 04.08.2017