The Race to Rescue the Rhino

I’ll never forget the moment I first saw an African rhino. It was sipping with its calf from a puddle on a marshy patch of southern Africa. It looked bulky, wrinkled, vaguely prehistoric, and utterly magnificent. It was also constantly on the radar of the armed guards who were roaming the nature reserve because this rhino, Thalo, was endowed with a horn that could fetch between $200,000 and $300,000 on the black markets of Asia.

“There’s a lot of poaching taking place,” said Opeo, the ranger who was guiding me, as we splashed through the swampland. “The rhino has become one of the most endangered animal species. Here we have armed guards 24 hours a day, but we never know when the poachers might come.”

Time Is Running Out

“The situation is dramatic”, says covert wildlife crime spymaster Andrea Crosta, whose group WildLeaks has established a well-protected whistle-blowing platform to help identify the major players in the illicit trade driving the slaughter.

Andrea Crosta

Over 7,000 rhino have been killed in the past decade in southern Africa and now there are only around 25,000 rhino left in Africa, and a further 4,000 in Asia. Do the maths; it is a ticking clock.

Rhino are vulnerable because of the extreme profitability of the horns and because, since they are much shorter than ivory tusks, they are easier to smuggle.

“The horn is extremely portable,” explains Crosta. “Smugglers can hide a horn in a single backpack.”

Easily Sold Status Symbol

Another problem is the strength of the market in Asia. The sale of rhino horn is illegal, but in Vietnam and China, shops selling the horn, which remains a status symbol, are easy to find, and they are not even particularly secretive about their activities.

“If they trust you a little bit, then immediately they’ll show you the good stuff,” says Crosta, “and if they trust you a lot, then they open the safe and show you the really good stuff. If you are a wholesaler yourself or a carver you can buy a whole horn.”

Andrea Crosta

The battle that is raging over these horns has turned some of the world’s most famous national parks in to militarized zones. The rangers tasked with protecting the rhino have one of the most dangerous jobs in Africa.

“There are extreme risks,” says South Africa-based Julian Rademeyer of the wildlife protection group Traffic: “You have poachers, some of them fairly heavily armed with rifles and sometimes accompanied by foot soldiers with other weaponry to protect them from the rangers. There are frequent contacts in the bush particularly in areas like South Africa’s Kruger National Park which has become a hotspot for poaching.”

Poachers are just „cannon fodder“

The arrests and shootouts in the Kruger might be dramatic, but in terms of conservation goals they will probably be fruitless, fears Rademeyer. “The poachers themselves are cannon fodder for the criminal networks trafficking in rhino horn. They are easily replaceable.”

As long as there is endemic poverty in southern Africa, crime syndicates will always find new recruits to fill the gaps left by those killed or arrested. Rademeyer points out that more than 2,000 poachers have been arrested since 2010 in South Africa, home to 79% of the world’s rhino population, but in this time poaching incidents in the Kruger National Park have only increased.

Chris Cummins

Poverty plays a further role in destabilizing the situation for rhino: the governments in countries where poaching is rife have so many pressing problems to deal with that wildlife crime can seem like a distraction. “One of the tragedies of dealing with wildlife crime is that while on paper it is often designated as a priority crime, in reality it isn’t,” says Rademeyer. “Then it is aided and abetted by extensive corruption.”

Intelligence Work Is Key

Traffic expert Julian Rademeyer says the solution is to go after the prominent figures in the international crime syndicates – and that is where Andrea Crosta of WildLeaks comes in. He’s is a sort of anti-wildlife crime spy master, gathering information and evidence about the trafficking system and sharing it, free of charge, with law enforcement agencies.

“In our opinion the key is intelligence work,” he says. “We run a network of informants and collaborators in different countries. You have to do most of your work covertly, not overtly, and try to find the right trustworthy officers in the right law enforcement agencies.”

The Elephant Protection League

That’s important because there are bad apples in influential positions. With so much money involved, corruption goes high up the chain. “We have rhino horn trader on camera talking to a member of our team about certain captains in the Chinese navy being involved in getting rhino horn into China. If you think about it, it is the best possible smuggling tool because they don’t get checked, for sure.”

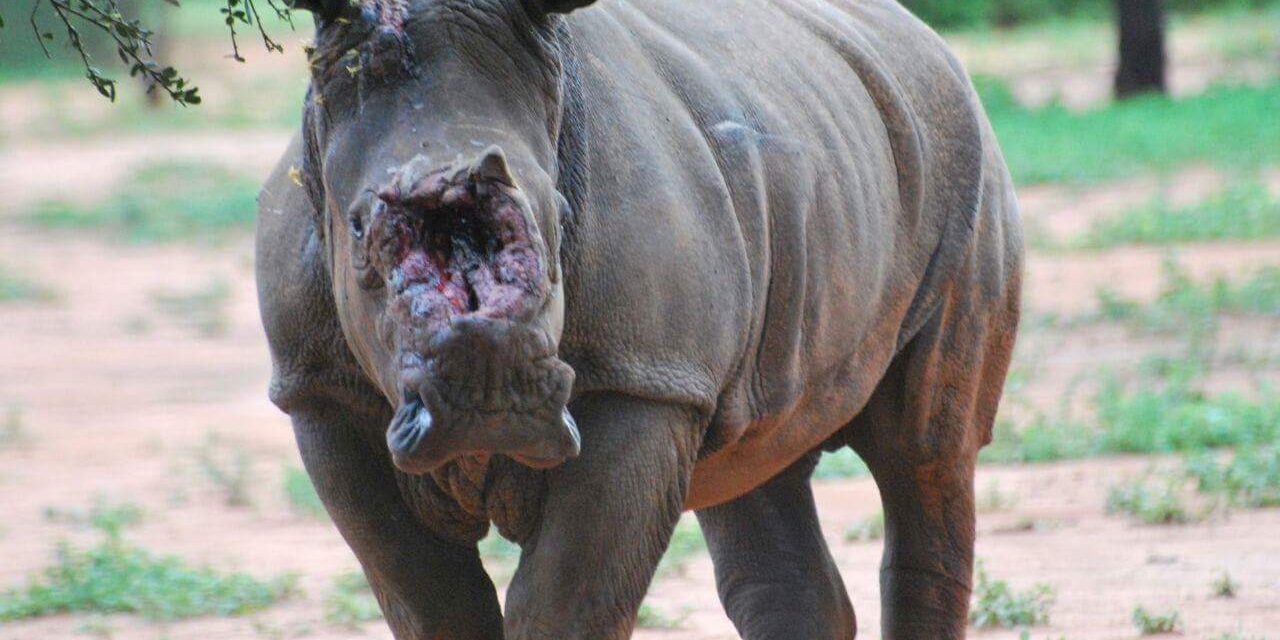

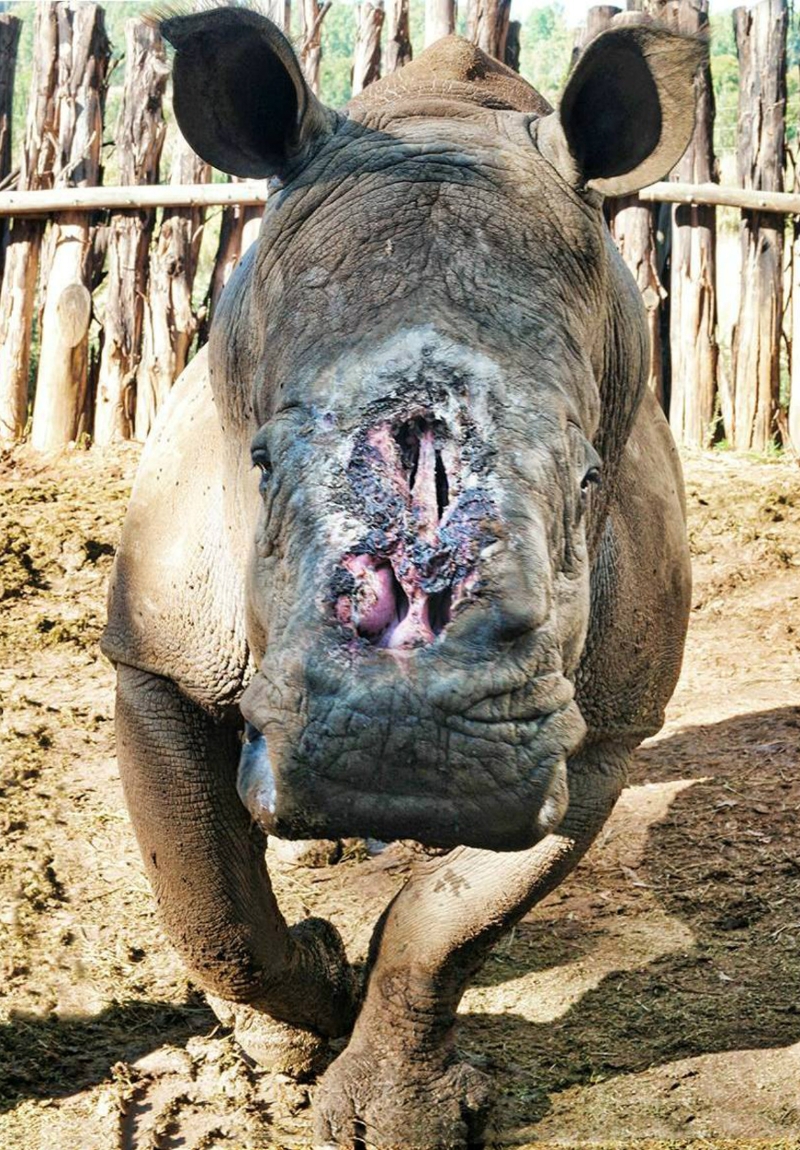

As Crosta pursues the kingpins, veterinary surgeon Dr Zoe Glyphis is patching up the wounds of injured rhino. Her group, Saving The Survivors, rushes to the scene of poaching incidents where rhino have been left alive but severely injured. “Most of them have been shot to bring them down and stun them, and then their faces have been hacked off. Some of them have had not just their horn but the underlying bones into their nasal cavity hacked off.”

It is always a race against time, sometimes involving a hasty flight from the group’s base just outside Pretoria. “We will get a call in from either a reserve, or from another vet, and we’ll pack the medical equipment, tranquilizer gun and set off to the scene. Every minute counts.”

Dr. Glyphis says it is “horrific” to see these huge, gracious animals so mutilated by human beings. The wounds are slow to heal and the work to save them is painstaking and dangerous, involving lots of patience and lots of tranquilizers. She says she is driven on by the success they have had: “The first rhino cow we saved has already had her second calf. We keep going because we know we can make a difference.”

Saving The Survivors

The efforts of the Saving the Survivors team are heroic, as are the sacrifices made by the game wardens and rangers, but the key to stemming the killing lies in breaking the market in Asia.

It might seem simple to disabuse consumers of the myths surrounding rhino horn. In Asia, the horn is often ground into powder and dissolved in wine, as there it is believed to increase sexual performance or even cure terminal cancer, but this is clearly nonsense. Rhino horn is made of a substance very similar to keratin of human finger-nails.

Stigmatizing The Sale

However, explaining the lack of any scientific basis for these claims of miraculous properties, and pointing out that customers have wasted hundreds of dollars to drink down powered finger nails, rarely works.

“Chinese and Asian consumers see an intangible quality in rhino that is really difficult to take away,” says Crosta. Campaigners are coming up against a belief system akin to the medieval belief in the power of relics.

Besides, rhino horn has become a status symbol, a sign on wealth and influence. In some circles, the illegality makes it more alluring; to own rhino horn means to be beyond the reach of the law. Campaigns to stigmatize rhino horn might work in the long run by appealing to new generations of Asians but, given the high rates of poaching, time is one thing the campaigners don’t have.

Chris Cummins

“The struggle to save rhino from imminent extinction is a real emergency”, says Andrea Crosta. Clearly it is important to save these magnificent animals, who roamed the savannahs long before humans turned up, for their own intrinsic value, but there is also a wider issue at play too, says Rademeyer.

“In some ways they have become symbolic. If we can’t save charismatic animals like rhino or elephants, what can we save? The onslaught on wildlife is immense.

There’s trade in pangolins and reptiles. It’s an enormous global business and an extremely deadly one. This is in many ways a test. Can we get it right? And if we can’t get it right, what does that say about us?”

Publiziert am 16.11.2017