Rethinking Recycling: The circular economy is about longevity and repairability

We face a two-headed ecological and economic crisis in Europe and time is ticking away. It’s a crisis of scarcity and excess.

As resources of important raw materials are becoming depleted or inaccessible, we are building mountains of toxic or unbiodegradable waste that we don’t know what to do with.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

Waste Hypocrisy

The member states of the European Union have often made fine speeches on leading the world on environmental standards, patronizing poorer countries about their shabby, litter-filled streets and dirty plastic-clogged streams.

But we’ve got around the problem of our own plastic waste, for example, by exporting it to exactly those countries with cheaper labour costs.

Until recently, we used to ship 165 kilotons of plastic waste every month to China. Then, last year, much to Europe’s consternation, Beijing said no thanks, that’s enough.

Other countries, including Vietnam, followed suit and although the EU has managed to find new poorer countries to accept the trash, a large proportion of the waste is now stuck in Europe.

E-waste is even more problematic. Despite a UN treaty, banning the practice, a large proportion of our computers, televisions, mobile phones, printers, and electrical goods like refrigerators and air conditioning units end up being illegally traded and sent to West Africa and Asia.

The impact of this e-waste on West Africa was harrowingly documented in the Austrian film Welcome to Sodom which highlighted its poisonous impact on the people of Agbogbloshie in Ghana

„It Sends a Signal“

That the Chinese have taken a stand against receiving European waste might be a game-changer, suggests Jocelyn Blériot, executive officer of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation “It sends a signal. If we can’t deal with this, maybe we shouldn’t be producing it in the first place.”

Chris Cummins

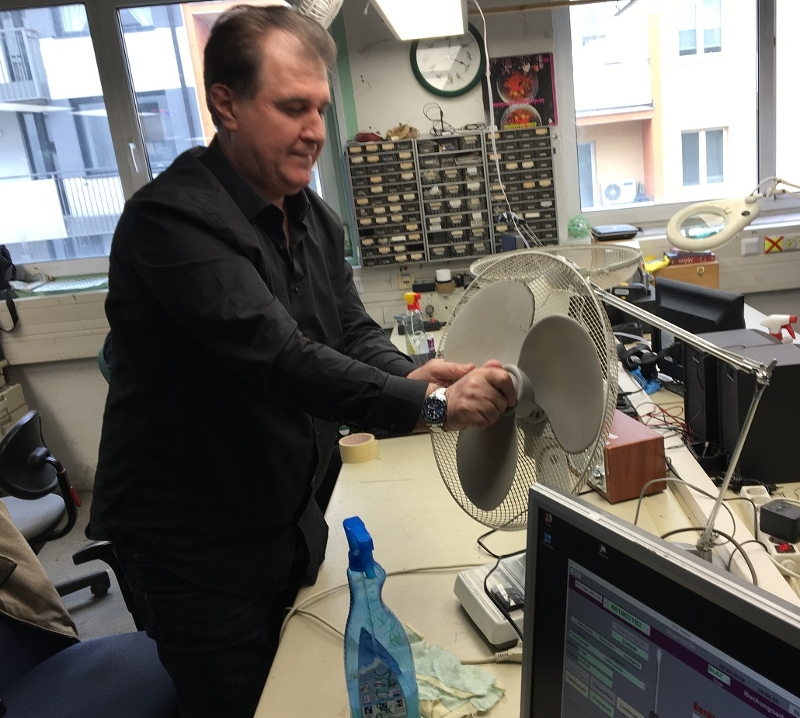

To understand the struggle to produce less waste, I head down to the DRZ, a noisy workshop in the 14th district of Vienna. If you throw away your electronic waste responsibly in Vienna, there is a good chance that it will end up at this workshop.

Six tons of discarded electronic appliances are brought here every day; from broken vacuum cleaners to worn out washing machines to old mobile phones. The team of workers on the shop floor weigh the junk and then dismantle it manually.

New Life

The workers have all been recruited from the lists of long-term unemployed at the AMS, the Austrian employment service. There’s a certainty poetry in this – no-one should feel they are on the economic scrap heap.

Katharina Lenz, a quality controller at the DRZ. was out of the job market herself before starting work at the recycling facility. “We give a new life to objects which have been discarded but we also give a new opportunity to people,” she says. “They come here on a short-term contract and gain new confidence through the work and support from our social workers.”

The first step on the shop floors is to open the casings and then to remove the polluting materials, which include lead, mercury, cadmium and beryllium, as well as hazardous chemicals, such as flame retardants. Then the parts that can be used to restore old or create new electronic goods are sent upstairs.

Chris Cummins

Recycling centres like these are an important aspect in efforts to create a more circular economy, says Miranda Schnitger, who works on a cities project at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, and who is looking around the DRZ with me. But, she insists, we also need to reconsider the who way we make things.

First Stop Rubbish Bin

“The thinking seems to stop at the point where your first need is serviced,” she says, “and after that when I no longer need the product I’ve bought, or I no longer want to wear the item of clothing I have bought, there’re aren’t that many opportunities to find a re-use opportunity for that. Broadly speaking, the bin is the first go-to point.”

Schnitger says this wasteful system makes no sense in environmental terms but also in economic and social terms. The circular economy is not simply an overly-intellectual way of saying recycling, it’s about designing products for longevity with repairability in mind so that materials can be easily dismantled and recycled.

The Slow Death of the Repair Industry

There seems to be a contradiction here. It’s the younger generations who seem most worried about the impact of waste, but the repair know-how of their parents’ generations is being lost. While the dad and grandpa would get out the screwdriver and fiddle, the son logs on to Amazon and orders a new one.

Chris Cummins

Correspondingly, the trusty-old repair shops are dying out, shuttering up and being replaced by cheap mobile phone outlets (and take away coffee emporiums). Schnitger blames this on design. “If you’ve ever tried to repair something these days it is almost impossible. The way design has evolved things are so beautifully sealed that actually getting into a product and figuring out how to repair it is an ability that is disappearing.”

An Aladdin’s cave

This negative trend is highlighted when we go upstairs in the DZA to explore what looks like an Aladdin’s cave for the electronically nostalgic. I see old hi-fis from the 1980s, classic speakers, vintage radios, even vacuum cleaners that look like they are from a period film. Among the aisles, there are some quiet geniuses fiddling with screwdrivers in the innards of the vintage electronic goods and bringing them back to life:

“These are people qualified as electronic engineers or microelectronics,” explains Katharina Lenz. “And they have a great passion for these things.”

Chris Cummins

It seems to me thought-provoking that people who have these amazing skills fell out of the labour market in the first place. In any case, the results they bring delight music geeks. The DMZ gets a third of its funding by selling the recycled products:

“These products are sometimes a few decades old,” says Lenz “and once repaired they will probably last for another couple of decades because things used to be made to last. These second-hand products are cheaper of course, but I think actually our customers come to us because of the quality.”

There’s also an arts and crafts room where the bowls of old washing machines are being transformed into bespoke baking bowls and where old floppy disks are becoming alarm clocks.

A Circular Pool of Resources

There’s a common misconception that adopting the principles of a more circular economy would prove ruinous to businesses. On the contrary, insist the concept’s supporters, it would benefit them. If they could invent a system to claim back and recycle the products they once sold, they would have access to a pool of raw materials.

Within a phone, for example, there are so many important resources that are dug out of the earth in environmentally-destructive mining operations. Electronics are full of valuable materials including copper, tin, iron, aluminum, fossil fuels, titanium, gold, and silver.

By throwing away your phone without it being recycled, you are forcing more extraction and at one point those resources will have disappeared. “You’re actually just burying the resources you need, tightly packed in a phone, into a landfill. It simply makes no economic sense.”

„Europe is a resource-poor continent“

You would perhaps have to be a particularly specialist Brussels watcher to have heard of the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan. It is a series of legislative proposals on waste to stimulate Europe’s transition towards a circular economy.

Jocelyn Blériot is not surprised that this has become a priority for the EU. We don’t have huge amounts of stuff to dig up here and nor to we have places to dump it. “Europe is a resource poor continent with not a lot of space,” he says. “We have to have that strategy in place in order to remain competitive.”

Blériot says companies are finally beginning to understand that they must think about the materials they use not just before the products hit the shops but also at the end of the products life.

“Taking a circular economy approach means that if it doesn’t fit anywhere afterwards, don’t put it on the market.”

Publiziert am 23.04.2019