FM4 Adventurous: „Go out there, explore, push the boundaries“

In 2003, as a student backpacker with an interest in journalism and Arab culture, Londoner Levison Wood turned up in war-torn Baghdad, a few months after the US invasion. His mum thought he was on a holiday in the Greek islands. He had to hitch-hike his way back out, heading north through Mosul with a convoy of mercenaries.

For some people that’s brave, for others it’s irresponsible foolhardiness that borders on lunacy. But nowadays Levison, who has made a career out of adventuring, looks back on those days with a fond smile: “I probably did do fairly reckless things when I was younger,” he says, “but at the same time it was those experiences that were very formative and which gave me the opportunity to do what I am doing now.”

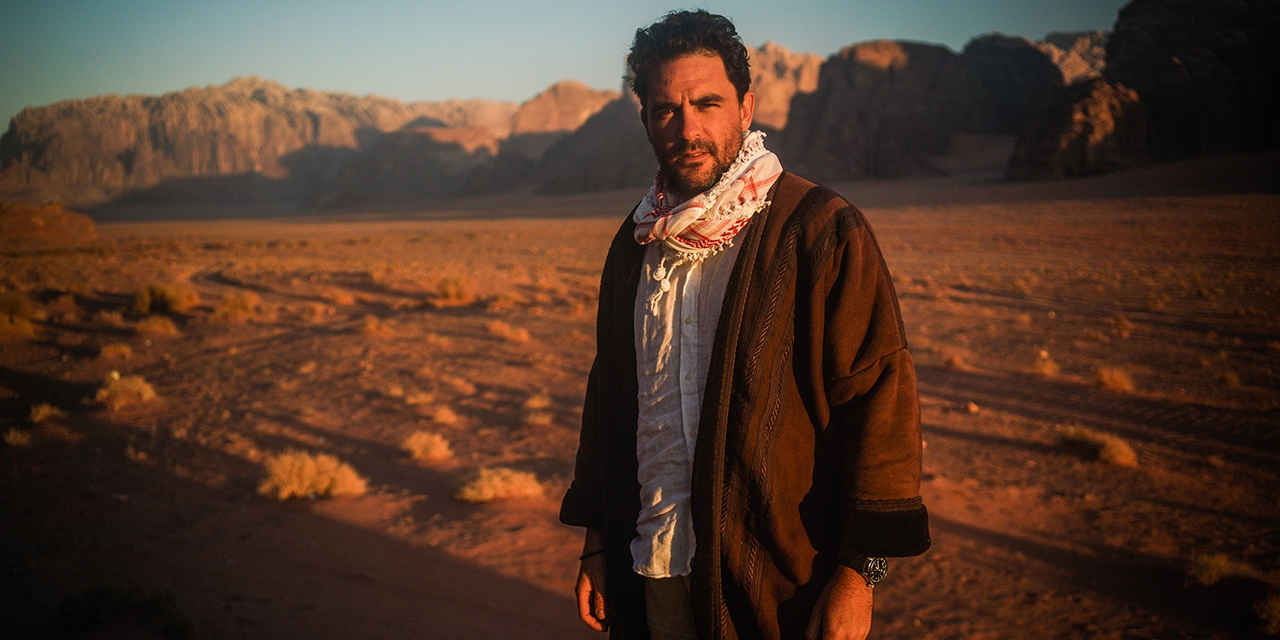

Levison Wood

Levison is the author of several travel adventure books, and a presenter of documentaries from paths less-trodden. “I don’t think I would have had the confidence to do what I am doing now, had I not travelled I those regions as a youngster,” he says.

After those early adventures as student journalist, Levison spent 5 years in the Parachute Regiment of the UK armed forces. In 2013, at a loose end after his return to civilian life, he embarked on what he calls a “now or never” expedition along the entire length of the Nile, from its source in Rwanda to the Egyptian coast. He followed that up with walks across the Himalayas, the Americas and the Caucasus Mountains, writing , filming, and cementing his reputation as of Europe’s hardiest adventurers.

FM4 Adventurous: Life Beyond The Horizon

This summer, at midnight on Wednesdays, on FM4 we will be meeting intrepid adventurers and asking why we have the urge to throw ourselves into the unknown.

We’ll be meeting some extraordinary people who have done some extraordinary things: sailed around the world, rowed across the Atlantic, climbed Everest, cycled across the Australian Outback, paddle-boarded the length of the Hudson river, or, in the case of my first guest Levison Wood who hiking down the Nile from its source to its delta, dodging bullets and sizzling under temperatures of over 50 degrees Celsius.

But it is not just about retelling stories of daring or exertion; it will be a summer long discussion about the human need to look beyond the horizon, despite the discomforts, expense and occasional dangers involved. Levison for one believes it is hard-wired into our brains; that our ancient ancestors knew that a sedentary life could never bring growth or development:

“You had to go other the next ridge,” he says. “Over the mountain, it’s true, you might find a sabre-toothed tiger, but you might also find more fertile soil and better water resources. Those who dared, prospered.”

You’ll find more on the series here

So why all this hiking? “I think there is something very simple about walking, and that is its appeal for me. It shows that adventure is accessible. You simply have to walk; anyone can do that. And by travelling on foot, by travelling at the slowest pace, you are forced to interact with people. In a car you can just drive by, on foot you can’t avoid people. You have these conversations and serendipitous encounters.”

Levison Wood

His latest trip, an 8,000km circumnavigation of Arabia, also involved lots of walking, although he also hitch-hiked and even rode on a tank. It was perhaps his most dangerous and controversial project yet. It took him into Yemen, Syria and Iraq, countries where, as he writes, “normalization of violence…made the place so bizarre, terrifying and alluring at the same time.”

Alluring? Is this a form of misery voyeurism? Should a man, known more as a news journalist than as an adventurer, go to these places, from where thousands are fleeing for their lives? Levison says he went in the spirit of a journalist, attempting to broaden the spectrum of insight we have into these war-zones:

“It was during the downfall of ISIS there was a lot going on, but I really wanted to shine a light on the more human aspects, rather than to look at the region through the media slant of current affairs and doom and gloom. I wanted to really go and draw out some of the human stories; the stories of people who aren’t interested in politics and religion and war.”

Hospitality Amid the Chaos

At their best, these passages are a way of reminding readers of the human tragedy behind the political mess; adding the colour between the abbreviated black lines of new reporting. Amid the chaos Levison encounters, people are still getting the groceries, gossiping over endless cups of tea, falling in love, getting married, and, almost universally, showing great generosity to the traveller.

In Sudan, notes Levison, locals “would rather die than not give a guest a meal”.

These simple encounters help generate empathy with the victims of the chaos, as fellow human beings who share our foibles, dreams and eccentricities. News gathering rarely achieves this.

Levison Wood

Still, even if he is convinced this form of reportage is “an important part of my work,” Levison’s journey took him to places where stray bullets were flying, and where kidnappings were rife. So I asked him whether he feared appearing in an orange jump-suit in one of those notorious hostage beheading videos?

“You have to be very unlucky for something like that to happen,” he replies. “Understanding the concept of risk has been the meat of my job for the past 15 years. I was very confident when I went to the front line in places like Iraq and Syria that I had surrounded myself with the right people.” He rode towards the frontline in the battle against ISIS on a tank with the Shia Hashd militia, striking a pose that many traditional journalists might find self-indulgent, but he says that he was travelling with people he trusted, and it was the best way to stay safe.

Risk Means Growth

Besides, he adds: “I always encourage people go out there, push the boundaries, be a bit of a maverick and see things for yourself.”* The concept of acceptable danger is a theme that Levison has dwelt upon. He worries that we are becoming stunted as a society by our obsession with staying safe; and that is something that begins even in children’s playgrounds:

“We do tend to shy away from risk in modern society,” says Levison. “While bad things can and do happen, I don’t think the negatives should outweigh the positives when it comes to assessing risk, because if we shy away from everything, we never develop, we never grow, we never learn new things.”

That said, when bad things happen, and you are far from the comfort blanket of society, you have to be open-eyed about the dire consequences.

On Levison’s first big adventure hiking down the Nile, which he filmed, tragedy struck early in the expedition. He had been joined in northern Uganda by the American journalist Matt Power, who had planned to accompany Levison on his hike for a few days and then write a magazine article about the endeavour. Two days into their time together, walking on dried mud in 46-degree heat, Power collapsed with heat stroke and died before any rescuers could reach the remote location.

“I look back and think if there was anything I could have done. But there wasn’t really, once Matt had decided that he would be there.”

Shaken up by the experience, Levison decided to continue nonetheless, but in the next country he visited, South Sudan, civil war broke out. “I saw first hand some of the tragedies that were going on, including mass graves” he recalls. “I was in a place called Bor when one of the rebel groups attacked a refugee camp killing 60 people. It was a real tragedy.” He was caught up in the gunfire himself, when rebels surrounded the city and started firing into it. “There wasn’t much to do,” he says, “other than try to hide out and wait for it to finish.”

Trekking across the globe has brought its surprises too. While hiking in the notoriously dangerous Darien Gap - a remote, roadless swath of jungle on the border of Panama and Colombia - Levison met tribesmen living in bamboo huts in the middle of the jungle “a couple of days upstream from the nearest village.” They were wearing grass skirts, but each had a mobile phone. “There was no signal, so I asked them what they used their phones for? They said that every couple of weeks we get in our canoes, go down the river to the nearest village and check into Facebook.”

Now in his late 30s, Levison says he has reached full circle with the risk-filled adventures that have made his name. His travels for the book and documentary Arabia took him back as a seasoned-traveller to the places he had seen as a wide-eyed teenager. Maybe now, it is time to look for different, calmer adventures. “I still am still fascinated by travel and I will continue to travel but perhaps in different ways.”

Publiziert am 10.07.2019