The Loss of a Moral Compass

When I woke this morning to the news of John le Carré’s death, I felt sick in my stomach with grief. At the age of 89, it can hardly be called a shock; and I had never met the reclusive writer in person. But the writer, whose real name was David Cornwell, had provided a complex moral compass during my entire adult life.

He novels were an exploration of the complicated global world we live in and my home country Britain’s role in it. There was both cynicism and warmth in his writing; there was the large scope of geopolitics and the detailed observation of human foibles.

Above all, his writing was a powerful, eloquent appeal for more humanity in a world obsessed with pragmatic realpolitik.

Continued Relevance

Le Carré was already an old man when I started reading his books at the turn of this century. He was 50 years older than me, but his writing felt fresh and relevant right to the end, dramatizing the political issues of the day in a way that made them easily digestible and haunting.

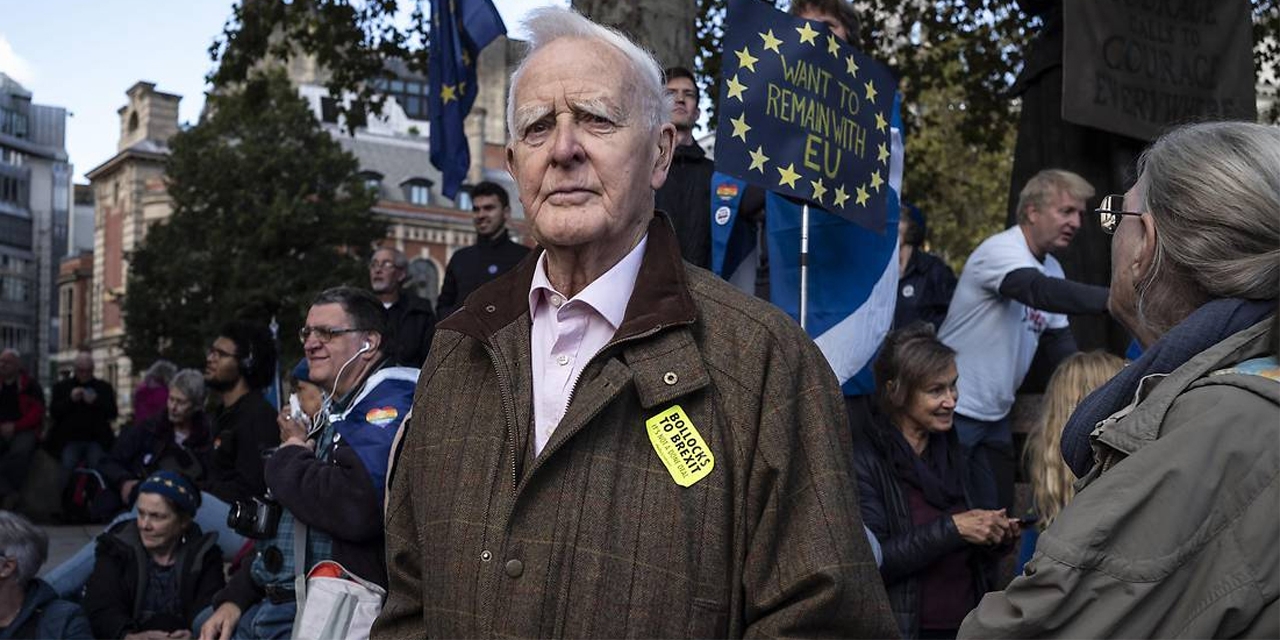

He studied German at university and was a passionate European with a particular fondness for all things Germanic – a passion he gave to his most famous fictional creation George Smiley. Last year, he published Agent Running In The Field, a novel that encapsulated the younger British generation’s anger, frustration and sense of alienation over Brexit. He was even seen personally at anti-Brexit rallies.

Black Lives Matter

I came to John le Carré novels well after the end of the Cold War that had made him famous. I read „The Constant Gardener“ (2001), set in turn-of-the-century Africa during the several months I spent in Africa myself. I was utterly captivated by his subtle bubbling anger that so many decades after the end of colonialism, Western lives were considered more valuable than African lives and how the profit of multinationals would trump the human rights of the most vulnerable.

The dark forces were perhaps led by untouchable amoral executives in shiny glass buildings far away, but they were aided and abetted by the almost touching weakness of the middle-ranking officials. These characters, such as embassy workers Sandy Woodrow, are humiliated by thwarted ambition, drunken, unlucky in love, seedy like the far-flung characters of his hero Graham Greene, utterly believable and tragically human.

And in „The Constant Gardener“ I found a template that runs through John le Carré’s work: the hero or heroine who dares take on power rarely, if ever, wins. Their only pyrrhic victory is to keep their sense of humanity in a cold world driven by profit or ideology that has forgotten its own humanitarian values.

His underestimated „The Mission Song“, which he wrote in 2006, when I was still deep in my African obsession, illuminated the chaos and destructive international interference in Kivu in northern DR Congo. Told through the worm’s eye view from a local translator, it brings a complex but vital ongoing story vibrantly alive.

The War On Terror

Through this century, le Carré, whose books were often translated onto Hollywood screens provided believable dramas that shed light on complex news stories. „Absolute Friends“ (2004) and „A Most Wanted Man“ (2008) dealt with “extraordinary rendition”, or more bluntly put, state-approved kidnapping; the excesses of the US-led „War on Terror“ and a creepy fear of Islam that pitted human rights lawyers against government institutions.

„Our Kind of Traitor“ (2010) dealt with the brutality of Putin’s Russia, its alleged association with organized crime and Britain’s readiness to turn a blind eye.

The Antidote to Bond

It was only when I had run out of contemporary novels that I explored the classics that had made John le Carré’s name. He was still working as a spy himself (hence the penname) when he published the first three novels in the early 1960s.

Set in grey back offices, they introduced a chubby, self-doubting intellectual, George Smiley who is serially betrayed by his wife and remains unconvinced by the value of the work he has dedicated his life to.

The novels’ very grubbiness and their depiction of departmental incompetence provided an instantly believable antidote to the fantasy glamour of Ian Fleming’s womanizing James Bond.

How Are The Good Guys?

In a way, he was a victim of his own success. He was still in the secret service when he wrote his signature book „A Spy Who Came In From The Cold“. It is fiendishly complex and utterly gripping and made him a household name; while asking difficult questions about Cold War certainties. “We’re all the same, you know, that’s the joke,” declares the East German spy Fiedler to the British spy Alex Leamas.

The West is just as cruel as the East in its espionage mission, abandoning people, sacrificing agents, lying. How do you justify this if you feel you are morally superior to the “bad” communists?

The boss, Control, justifies it like this: „We do disagreeable things so that ordinary people here and elsewhere can sleep safely in their beds at night.“ But on the front line the moral ambiguity is too much too bear for Leamas.

A Real Life Spy Legacy

Carré had viewed the plot as convoluted and unbelievable; an interesting drama to explore ideas of compromise and ideology and was shocked that, similar to Netflix’ „The Crown“ this year, people interpreted it the real inside story. Le Carré depiction of espionage would influence the way generations would view the security forces much to the frustration, apparently of those involved. His time writing from “the inside” was over.

Nonetheless several terms he invented for his novels like Lamplighters, Scalphunters and Janitors have entered the real vocabulary of espionage.

A Lonely Bookish Boy

It is his novel „Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy“ that I love the most and for one particular reason. It is touching as a story of the victims of an ideological struggle once seen as glorious, now seen as exhausting, tawdry and compromised. World-weary George Smiley (played by Gary Oldman in the 2011 film version) is back, along with alcoholic ex-researcher Connie Sachs who is missing “her boys”. There are front line spies, Jim Prideaux and Ricki Tarr who have been brutalized and abandoned and are now distrusted.

But the secret hero is a little boy, Bill, the odd-one-out at a boarding school, watchful and lonely searching for a father figure.

After a career of reticence on his own life, David Cornwell/John le Carré published his autobiography „The Pigeon Tunnel“, finally discussing his lonely childhood, physically abandoned by his actor mother when he was 5 years old and alienated from his conman father. The bookish little boy Bill, wise beyond his years and aching for company seems like a heart-breaking self-portrait.

A Missed Opportunity

Having been a Cold Warrier himself, and followed the struggle of the West against the East for decades, Le Carré didn’t experience the fall of the Iron Curtain as a triumph but rather than a missed opportunity.

He feels the West should have embraced Russia, massively invested in its future and led exchange programmes so that the young generations could meet and come and understand each other. „Decent nations should be a family,“ he told the BBC. „We did next to nothing.“

„The British public has been bamboozled“

But it was his disgust at Brexit that led the naturally shy author to be at his most outspoken. He reviled the nationalism that the Leave campaign had used, creating enemies from nowhere. „I feel strongly that British public has been bamboozled by people with private interests“

“I think my own ties to England were hugely loosened over the last few years,” he told The Guardian last year. “And it’s a kind of liberation, if a sad kind.” But in a period when Brexiteers have been trumpeting a sense of Englishness that I find alienating and disturbing, he was quintessentially English in a way I admire.

He was intellectually erudite with a beating social heart, he was cynical about the corrupting influence of power and money but hopeful about personal relations and individual heroism.

The Best Sort Of Englishman

It feels to me today that part of the English soul, so far from the bull-dog blustering of Farage and Johnson, died this weekend. And just when he was needed most.

He announced that „Agent Running In The Field“ would be his final novel. I didn’t believe him; like so many readers, I was yearning for the next.

Publiziert am 14.12.2020