Kindertransport Veteran Hella Pick’s Remarkable Life

At the age of just nine, Hella Pick was put on a train by her mother and sent away from her home of Vienna. She was off to London, alone, to be picked up by strangers in a country where she didn’t even speak the language. It was a heart-breaking but necessary separation.

But it was spring 1939, the Picks were Jewish and Nazi terror was getting more and more deadly. Her mother decided that the best way to help her little girl survive was to send her away on the Kindertransport trains that had been initiated as a response to the horror of the Kristallnacht.

How would you feel as a parent having to make this anti-intuitive decision? I hope I will never know. How must it have felt to be that lonely child?

Meeting a Zeitzeugin

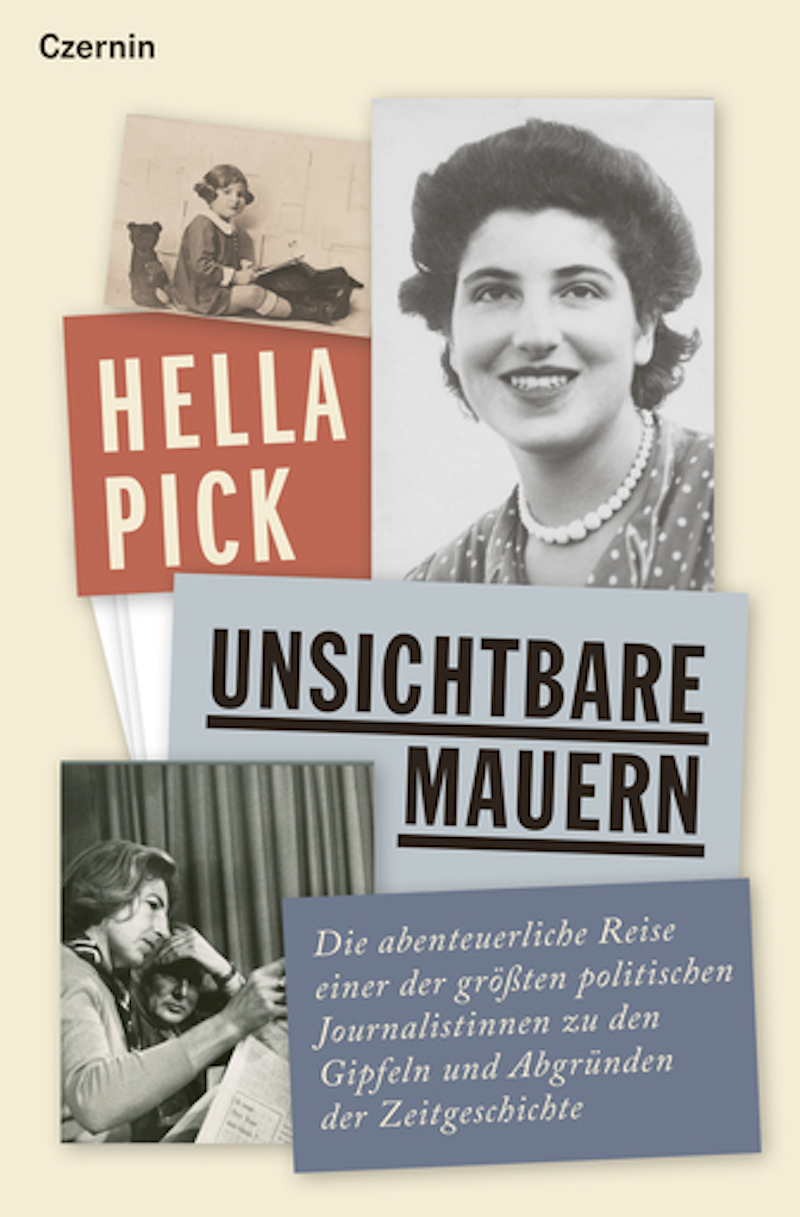

Czernin Verlag

Wer mehr wissen möchte: Hella Pick: Unsichtbare Mauern. Autobiografie. ist im Czernin Verlag erschienen.

I asked Hella, who is at the British Embassy event in Vienna to commemorate the Kinderstransport. She admits that her memories of that journey to London are vague. It was 85 years ago. But she does remember the health checks on the boat that took the children over the English Channel. “On the last stage of the journey we were all physically examined yet again,” she told me this week, “because of the British group who were sponsoring the Kindertransport insisted that the only children who were 100% fit should be allowed into Britain.”

I was shocked to hear this sub-plot of the Kindertransport story that has been celebrated, justifiably, as a story of generous humanity. Over nine months, the Kindertransport, which began this week 85 years ago, brought around 10,000 mostly Jewish children to relative safety in Britain, before the route was closed by the outbreak of full-scale war in September 1939. But the programme clearly involved some quite brutal restrictions, remembers Hella: “If you weren’t healthy in any way or even had any records of suicide in the family, you were denied entry.”

„Hello. Goodbye“

After arriving in London at Liverpool Street Station, she was taken in by a Jewish couple called the Infields, who had three children of their own. She greeted her new “family” with the word “goodbye”. It was, after all, the only English word she knew.

Nonetheless, Hella somehow thrived. She says she adapted quickly to being in England and her first school report, after just a few weeks, showed she was already conversing in English. Hella describes the family as “generous”. Indeed the Infields would have adopted her formerly, but 3 months after Hella’s arrival her mother gained a visa as a “domestic worker” – one of the only routes available to Jewish adult refugees – and started cooking for a professor at the London School of Economics called Theo Chorley.

A Lake District Springboard

Chorley, clearly a man of good tastes, was a fan of Austrian food and was very happy to have a Viennese cook. Hella was reunited with her mother at the Chorley family home in the beautiful English Lake District. It must have been strange becoming a servant in an English family having lived a middle-class life in Vienna but the Picks were coper and the Chorley’s were kind.

“They were immediately very friendly towards me and somehow took me on board as well,” Hella remembers.

This new home with an intellectual family was a springboard to a good education and then a remarkable career as a foreign correspondent where she blazed a trail in an once macho-world where women were largely expected to type up stories written by star male journalists. There were figures such as Martha Gellhorn breaking the mould, but Pick was truly a courageous trail-blazer – a triple outsider as, as she puts it “a refugee, a Jew and a woman.”

The Insecurity of The Refugee

Along with the necessary portion of luck, she says there was an intense drive that she feels is common among refugees: “I think the rupture from Austria made me determined to make a success,” she tells me as she leans back in the plush chair at the British Embassy. “I was a good learner at school, and I was absolutely determined to get myself to university. And I think I’ve always been driven by the need to demonstrate that, despite my insecurities, I can succeed.”

It’s hard to imagine this feisty 94-year-old as having even been insecure, but she insists that insecurity plagues refugees, whatever they achieve. “Many years later, I ended up working for George Weidenfeld, who was of Austrian origin like me, who had made a great success as a publisher,” she tells me. “He won made many British honours and yet felt insecurity all his life. It is this business of trying to demonstrate to yourself that you can do things in spite of anything that might be against you. I think there is a certain drive that comes with it.”

The Highlife in West Africa

Hella and I have one thing in common; we both started our journalistic careers in West Africa, a vibrant world of vivid colours, warmth and highlife music. It was the 1950s, she had picked up a job for a publication in the Daily Mirror group and was right in the centre of events as wave of optimistic independence movements signalled the end of the colonial era.

“I came in as a newly minted journalist,” she remembers; “I was the only woman amongst the small group of European American journalists who were covering those negotiations and writing about those countries’ ambitions. And I was on a learning curve.”

There was snobbery and sexism but there was also useful flirtation. Hella gleefully admits to using her beauty to wrap press-speakers and politicians around her little finger. She describes the late Ghanaian independence leader Kwame Nkrumah as a friend and describes working conditions that journalists like me can only dream about nowadays. “All those people were totally accessible in those days,” she remembers. “And of course, there was very little security. You could just have the phone numbers; or you knew where their residence was and you met them. No problem.”

A Dream Gone Sour

After experiencing this “heady” days of seemingly unlimited opportunity, Hella casts her eyes down in sorrow when she thinks of what has become of the promises of independence 70 years on: “A lot of that initial leadership really believed the concept of Africa, and they really thought they could turn the African continent into a prosperous, developing world, full of countries collaborating with each other.”

Since then, she has watched those hopes fall apart. “And at the time, I think nobody realised how important religion would be. The role of fundamentalism was not recognised,” she tells me. “Tribalism, although it was recognised, wasn’t seen as quite such a problem as it has since become.”

Falling Into JFKs Arms

Her stint in Africa helped earn her the job of diplomatic correspondent for The Guardian and she was there at key moments in 20th Century history. During a period in the USA, she literally fell into President JF Kennedy’s arms and she walked with the 30,0000 demonstrators on the Selma Montgomery Voting Rights March and risked her life by giving a black colleague a ride in her car.

The Cold War

By the 1970s she was Eastern Europe correspondent behind the Iron Curtain in Poland and Romania. She drank champagne in a Gdansk church with Solidarity Leader Lech Wałęsa to celebrate the Nobel Peace Prize he had been awarded in absentia. She saw the Polish Pope’s first visit back to his home-country and felt then communism couldn’t contain the people’s desire to think, believe and act with freedom.

Hella even got to interview Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, an absurd man and an absurd interview. She had to agree questions and promise to come “smartly dressed in stockings” and when she met the little dictator - “a nasty little man” - he had a barricade between them “I suppose so I didn’t physically attack him.”

Ceausescu had an interpreter, but Hella did not. “He started reading questions from pieces of paper,” she recalls. “They were not translated to me. After the sort of first or second answer to my two questions, I decided to ask a question that was not on the list. His interpreter was baffled. But Ceausescu just pulled out his next piece of paper and started reading from it. I have no idea what was on his piece of paper, but it certainly wasn’t the answer to my question.”

Reconciled with Austria

After fleeing Austria in such dreadful circumstances, you might expect a frosty relationship with her original homeland – but Hella says she comes back often and loves Vienna. She’s written a book about Austria called Guilty Victim and says we must be constantly vigilant about the rise of hate. Spikes in anti-Semitism are a concern but generally she feels proudly at home:

“I’ve spent more and more time in Austria as the years have gone by,” she tells me. “I came here on holidays as soon as I saw this was possible after the war to come back to Austria. “At first, I started writing about Austria for The Guardian newspaper. At first, I always felt like a tourist or a working visitor. But today, when I come to Austria, I feel totally at home. And, you know, I’m as happy, as I am in England in some degree. I feel here because Britain, since Brexit, has acquired a certain character that alienates a lot of people like me.”

Publiziert am 06.12.2023