Save The Whales To Save The Planet

We are searching the seven continents for solutions for the climate crisis; for example planning to plant billions of trees. That’s good. But we’d be wise to also look beneath the waves of the oceans that separate the landmasses. Imagine the Earth as having two lungs, like we humans. Our beleaguered forests are one of them. The other is the plankton in our oceans.

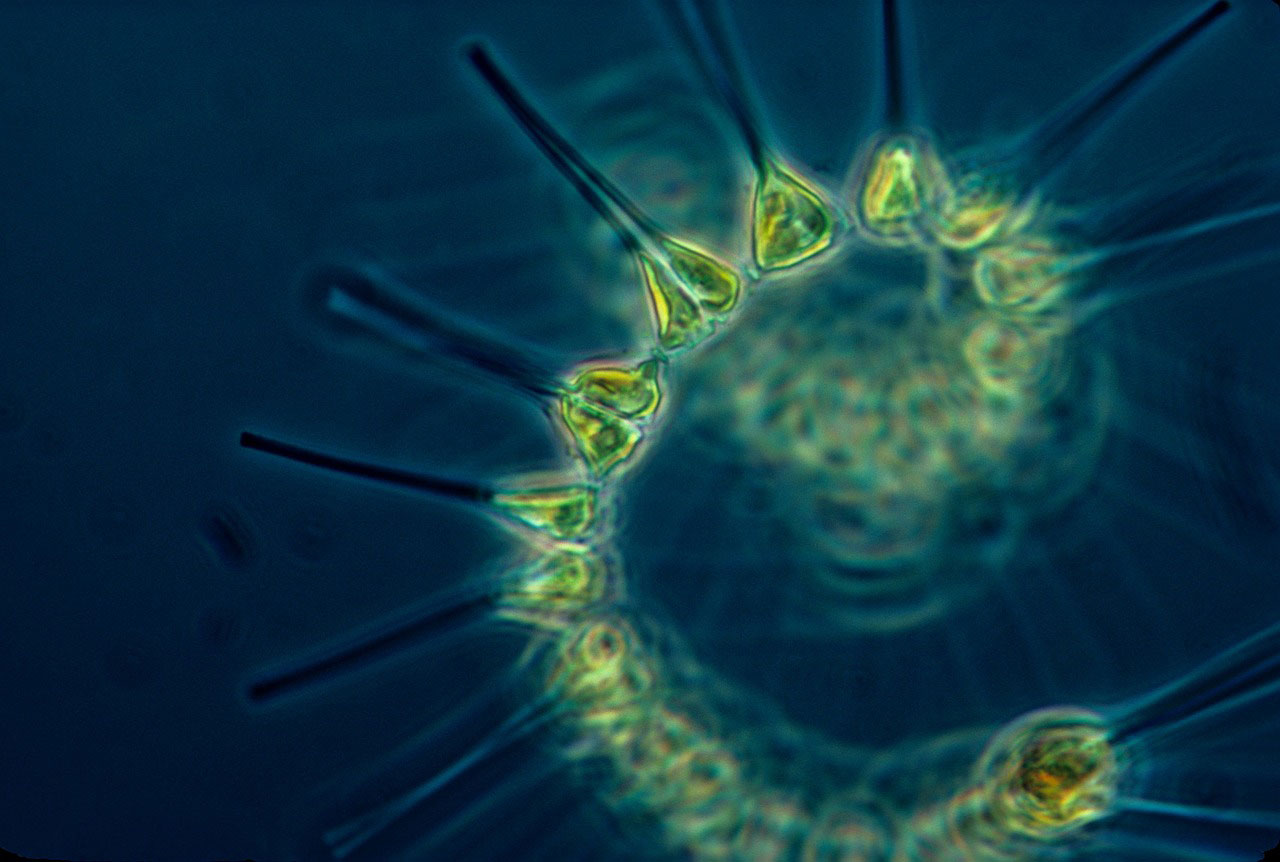

We rarely talk about phytoplankton or even think about it. You won’t see phytoplankton mentioned or drawn on banners at Fridays For Future demos, you don’t go on holiday to see it and yet these microorganisms that absorb carbon from the sky via photosynthesis are at least equally as important as rainforests.

“Every year phytoplankton absorbs at least as much carbon dioxide as four Amazon forests,” explains Ralph Chami, an IMF economist, “that’s how important they are.” In aggregate phytoplankton captures the same amount of carbon as 1.7 trillion trees.

CC0 via Pixabay

Phytoplankton

A Life-Changing Trip

Why is an economist banging on about phytoplankton? Well it’s all to do with his love of whales, which, it turns out, play a vital role in nourishing the microalgae. Chami went on a sort of study-holiday; joining scientists of the Great Whale Conservancy on a ship in the Sea of Cortez off Mexico observing the giants of the sea.

He became entranced by the scientist’s explanations of the whale’s role in maintaining ocean health and wondered why it wasn’t more widely discussed in the public conversation about the climate crisis. He realized that of all the numbers he had crunched through his life, none were as vital as these life-giving equations.

It’s in our self-interest to save the whales. As well as preserving rainforests, we need phytoplankton to flourish. Now, for phytoplankton to flourish, we need lots of whales. But, while in plain sight we are burning and logging our rainforests, we are also decimating populations of whales in a mass killing that is rarely seen and is little understood.

CC0 via Pixabay

Poo Power

Like many of my favourite subjects these days, this story is all about poo. The excrement of cetaceans provides a rich plume of the three vital nutrients that phytoplankton need to survive phosphorus, nitrogen and iron. The plankton get some of this holy trio from run-off from rivers and also wind movement over land but in many parts of the oceans it is only the whales and their poo that keep the Earth’s underwater lung working.

“What we observe in satellite imagery is that the phytoplankton is very active in the area where the whales exist,” explains Chami, “and where there are producing a lot of poop.” Indeed, it turns out that there is a deeply symbiotic relationship between whales and this phytoplankton. Wales feed on krill, which feed on phytoplankton, which need whale poo: It’s a neat circle that is typical of nature. Whales are fertilizing the oceans and their own food sources.

Taking Carbon To The Grave

And not only do whales fuel the Earth’s lungs, they are also massive carbon sinks themselves. Over their lifetime they collect carbon in their tissues and bones (as do we, but we are not nearly as big). “On average we estimate that whales capture about nine tons of carbon and when that whale dies it sinks to the bottom of the ocean and it stays there for a very long time.” Nine tons of carbon are the equivalent of 33 tons of carbon dioxide and that is the equivalent of many thousands of trees, which typically absorb just 21kg of carbon every year.

Given this dual role, says Chami “one whale is worth thousands of trees.” If we can save the whales, we might just be able to save ourselves. And yet we are doing the exact opposite.

Ship Strikes and Net Strangulations

Scientists believe we used to have four to five million in pre-industrialized times but now we have just a quarter of that. And it’s not the same across all species; while some species like the humpbacks have been able to stabilize their populations, the right whales have been decimated and now there are only a few hundred left.

“Most of them are no longer dying from whaling,” says Chami, “many of them are being killed by ship strikes or being destroyed internally by seismic testing or sonar testing or they get caught in nets.”

$2million Dollar Whales

Being an economist, he’s put a price tag on a living whale of $2million not in a vulgar attempt to monetarize priceless biodiversity but rather to persuade politicians and stake-holders what we are wasting when we kill them though carelessness and greed.

Think of the REDD+ scheme. That UN conservation mechanism is deeply flawed, but its central aim is sensible: to persuade stakeholders that a rainforest is worth more as a living carbon sink and water tap than it is worth as lifeless timber, Chami hopes that if we understand the value of whales in our planet’s breathing apparatus, we might start making sensible decisions on protecting them.

“Appealing to people’s better nature hasn’t really helped that much,” he says, “so putting a price on them is basically saying they are worth a lot more alive than dead.

Some Hope

One big problem is that the deaths of the whales usually go unnoticed. When an elephant is killed on the African savannah we are left with gruesome, fly-covered corpses that shock our consciences. But when a whale is struck by a ship, it will typically sink to the bottom of the ocean, out of sight out of mind.

This is all very depressing but there are some positive examples of political will changing the narrative. Just outside the Boston harbour there were pods of humpbacks who would come to feed and get hit by ships. The authorities diverted shipping lanes by just 60 degrees and the death rate for the whales dropped by 80%.

“Whales are like elephants,” explains Chami. “They are creatures of habit. We know their migratory routes, we can track them via satellite, and we have detailed data on shipping lanes. So we just have superimpose it and figure out where the strikes are.” He says that a minimal adjustment to shipping routes could have big impact on saving the lives of whales.

“The story of the whales is the story of us. The story of the whales is the story of the planet. They were there millions of years ago and they have been looking after us quietly in the seas,” says Chami. “Now it is our turn to look after them. Life is about give and take. We have to give back by simply letting them live.”

Publiziert am 17.01.2020