Has The Nuclear Waste Issue Been Solved?

I’ve found a way of silencing conversation at a party in Austria. It’s a way to alienate environmental allies. If you openly muse aloud on whether it is possible to avoid catastrophic climate change without maintaining and even expanding the number of nuclear power plants globally, you are likely to get the social equivalent of an apocalyptic nuclear silence.

Nuclear power is not popular in Austria.

Ever since the Austrian public very narrowly decided in a 1978 referendum to cancel the start-up of its first nuclear power plant az Zwentendorf (50.47% voted against the start-up), this county has become more and more united in its opposition to nuclear power.

APA/dpa/Armin Weigel

Not Everyone Has Austria’s Advantages

When energy and climate minister Leonore Gewessler announced Austria was ready to go to court if the EU decides to include nuclear power into the bloc’s taxonomy on sustainable finance, the move met much approval. On a political and social level, Austria does not like nuclear power.

In a way though, points out professor Michael Bluck, Austria is in a privileged position to be able to reject nuclear. “Austria is in a safe space. It’s got hydro. It doesn’t need nuclear,” Bluck, the director of the Centre for Nuclear Engineering at Imperial College London told me. “Much like Norway, you have the elevation to make hydro storage and hydro work for you. Most countries haven’t got that.”

Nuclear Power or Climate Catastophe?

He argues that nuclear power plants generating carbon-free electricity day and night, windy or calm, and that any hope of winning the race against out of control temperature rises will require us to use every source of non-fossil fuel energy available. “Those who deny that,” he says, “are hoping for a new source of energy to come along in the future. But hope is not a strategy.”

APA/dpa/Thomas Frey

There is of course much disagreement on this matter.

Shaun Burnie, a nuclear specialist with Greenpeace insists that nuclear is a power source of the past, arguing that the wind and solar are becoming ever cheaper while the cost of nuclear continues to rise. He says the way modern grids work make a “nonsense” of the intermittency argument used against wind and solar.

But nuclear engineer Dr. Leslie Diwan points out that supply-chain issues might hold-up the rapid expansion of solar; we have to mine many of the minerals needed and China controls most of the production. It’s an issue that security expert Olivia Lazard told me, earlier this week, frankly terrifies her.

A „Little Cave“ in Finland

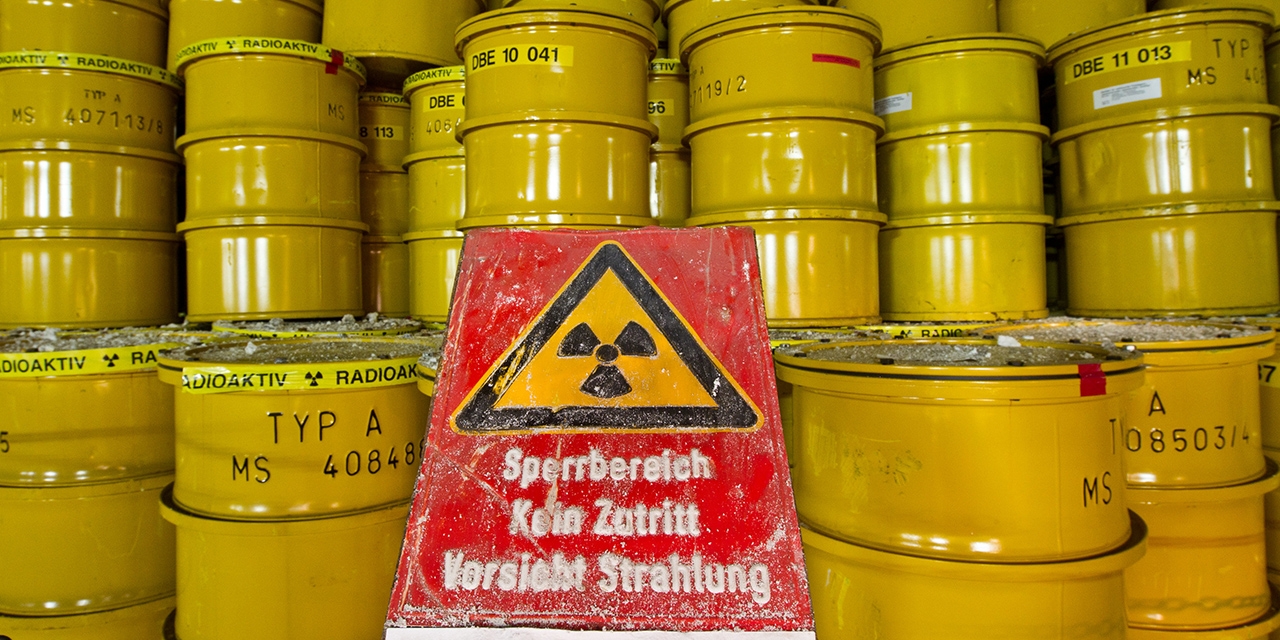

There is however one issue we have all been able to agree on. There is a major drawback to nuclear power that has seen it described as the “scourge of future generations”. We embarked on a global programme of nuclear energy production without actually having a feasible plan of what to do with the dangerous waste created by that process, a form of waste that can pose a threat to human health for 100,000 years. As elephants in the room go, that is a pretty hefty glowing elephant.

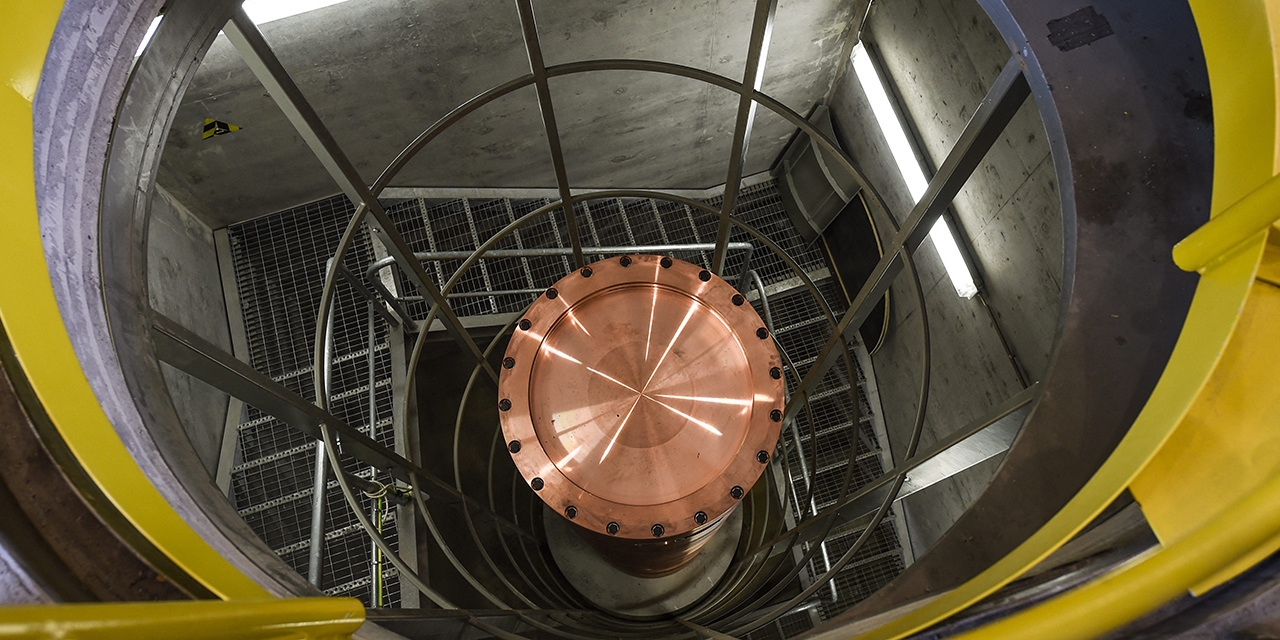

That’s why there has been a lot of buzz about a facility called Onkalo in Finland that is due to open next year. Pasi Tuohimaa, the head of communications for Posiva, the waste management company told Deutsche Welle “A lot of people say that, okay, nuclear is good, but then you have this waste of used nuclear fuel. What we are saying is that, no, that’s not true. We do have the solution for that and it’s completely safe.”

APA/dpa-Zentralbild/Jens Wolf

How Will It Work?

„Completely safe“ is an audacious claim. So let’s look at how it will work:

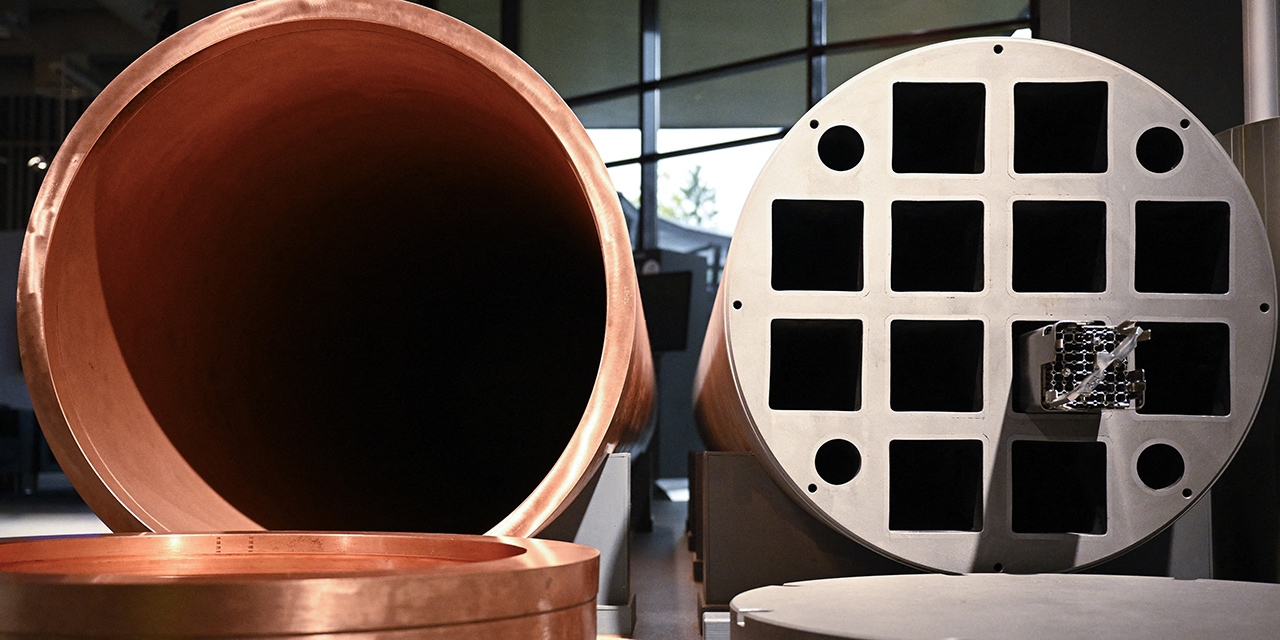

Spent nuclear fuel from Finland to nuclear power plants will be transported to the site at Onkalo, which means “Little Cave” in Finnish and then will be double packed. Firstly it is put into steel canisters which, in turn, are put into copper capsules. Those are then lowered into the carved out bedrock and packed in something called bentonite.

That’s basically the stuff we use as cat litter. The tunnel is then back-filled and sealed.

“This is to keep water away because water is the medium that can, in principle, transport stuff,” explains nuclear engineer Michael Bluck.

He says it is pretty hard to imagine a scenario in which the system fails, although making any predictions about 100,000 years is pretty much impossible. “You do what you can,” he concludes.

Indeed, says Michael, the remarkable thing is that the public is on board with the project. The biggest problem with nuclear disposal is the understandable mistrust of the local people.

APA/AFP/dpa/Julian Stratenschulte

It Won’t Work Everywhere

Dr. Leslie Diwan says similar projects in the US have been abandoned because of risks of earthquakes or oxidisation. But this project is different.

"It’s very stable geologically at Onkalo,” she explains. “It’s a granite bedrock that produces a chemically reducing environment that induces materials to remain stable on very long timescale. So, if you’re going to have a long term repository anywhere, the site is where you would plant.”

Inherent in her answer, of course, is the drawback for anyone hoping this is the silver bullet that frees up the nuclear energy industry. You can’t replicate this system in many regions where we have nuclear power; Japan for example.

Is It Really Safe?

Besides, Shaun Burnie, the nuclear specialist with Greenpeace is less convinced than Professor Michael Bluck of the long-term viability of the problem. “If a nuclear geological repository is to meet regulations,” he tells me. “They are supposed to demonstrate that radioactivity will not enter the biosphere over 100,000 years. Over the border in Sweden, the regulators and scientists have found that actually copper canisters are degrading within decades.”

APA/AFP/Lehtikuva/Emmi Korhonen

What is Radiation?

It seems to me we need a very rational, science-based discussion on these issues and that’s why it is important to take a big step back and look at what radiation is.

I say that because I knew nothing about it before I started researching for a trip to the area of Belarus affected by Chernobyl and was surprised to find that not only do we daily get a dose of background radiation, which increases as we climb up mountains (and of course take plane fights), that some areas such as Cornwall have elevated radiation levels because of their geology and that there is radiation in bananas and breakfast cereal.

We Need To Talk

This is not an attempt to trivialize the vital issue of high-level nuclear waste, it is to set a base-line understanding for people who, like me, get the heebie-jeebies when they see that yellow and black trefoil sign when they get a dental X-ray.

The heebie-jeebies are not helpful when trying to talk rationally about energy production and, given the apocalyptic scenario of runaway climate change, we have serious decisions to make.

Low-Level, Medium-Level, High-Level

When we talk about nuclear waste, what are we actually talking about?

“Look, there’s low level waste. That might be the smoke detector in your home or clothing used by workers in radiation. It’s below background,” explains nuclear engineer, Professor Michael Bluck. “Then there is intermediate level waste that arises from some of the structural components in a reactor when it is decommissioned. And so that’s higher level waste, but it’s not long lived waste.

Okay, that’s not too alarming. But then when we talk about nuclear waste in the media, the stuff that’s getting buried in Finland, for example, we’re talking about something very different.

“The stuff that people are worried about and we look to bury far away from people is the high level waste,” explain Michael. “And that’s a very small amount by volume when it comes freshly out of a reactor. It is hot and it is very radioactive."

APA/AFP/FRANCOIS NASCIMBENI

What has been done so far?

So we’ve heard how this project to store nuclear waste on the ground in Finland is somehow new and is being sold as an exciting breakthrough. Which begs the question what is a world been doing with its nuclear waste until now?

“So you start off by reprocessing your waste through a process known as vitrification,” explains Michael Bluck. You convert it into glass.And so nuclear waste looks like this sort of dark glass, like obsidian. And glass itself is extremely stable.”

Most of it is just stored above ground, or in cooling pools, awaiting a route to disposal. “At the moment, it’s sort of sitting with us,” says Michael. And this is a world where nuclear facilities get shelled by war-mongering Russians, is not a reassuring situation.

APA/AFP Olivier MORIN

Is Nuclear „Dirtier“ Than Other Sources?

Besides, I’m not sure I’m particularly reassured by the small volume of the lethal waste, since a small volume can still kill us. Mosquitos are smaller than puppy dogs, but I know which of the two I fear more. But nuclear engineer Dr. Leslie Diwan points out that it’s not just the nuclear power industry that has nasty by-products.

“It’s a good point about the volume,” she concedes. “But I guess it comes down to also, you know, if you look at the amount of mercury that’s released when you’re burning a metric ton of coal, if you’re looking actually at the amount of radiation, for example, when you’re burning fossil fuels, it ends up being pretty comparable to nuclear.”

The difference is, she says, that the nuclear industry at least accounts for these dangerous bi-products and is working on their safeguarding and disposal whereas in coal smoke they are simply released into the atmosphere.

A Fair Debate?

Professor Michael Bluck says that the dangers of nuclear waste are perhaps greater in the public perception than in reality. He says our fear of all things nuclear are tied up with our fear of nuclear weapons: the two things are inextricably linked in our minds.

“Look, there is no recorded instance where there has been any fatality due to nuclear waste,” he says. “Literally, nobody has died from the waste at all. If we include all of the deaths due to all of the accidents in the history of nuclear, you still got far less than all of the deaths due to mining of minerals for solar and PV.”

Let’s Look At The Facts

During the corona pandemic, we journalists have insisted on basing all decisions on known facts not fears we have seen repeated on the internet. Shouldn’t we take the same rational approach to discussing nuclear power?

400,000 Europeans die in Europe each year because of air pollution, often linked to fossil fuel burning through heating or combustion-engine vehicles, and yet we are not nearly as fearful of that threat as we are of the nuclear threat.

The Shadow of Fukushima

Okay, says Shaun Burnie of Greenpeace. Let’s take on the challenge. Let’s talk rationally about nuclear. Let’s talk about the true cost to society of this industry. Let’s talk about the hidden costs of maintaining nuclear waste with no end date in sight. And let’s talk about the cost, in human health, land and dollars when something goes terribly wrong:

“Let’s talk about the Fukushima disaster, which the industry doesn’t really want to talk about in terms of costs,” he suggests. “The official government estimate in Japan is around 120 or $140 billion. There’s independent assessments from think tanks in Japan say that it might be around 750 to $800 billion.”

When it comes to the future there are no magic solutions? Should nuclear be part of our path to avoid a climate catastrophe? What do you think?

MORE KLIMANEWS WEEKLY

Publiziert am 21.10.2022