Viennale: The easiest way to travel

by Johnny Bliss

As I write this, I have just seen my thirtieth movie of the Viennale this year, which was the intriguing Turkish drama “A Tale of Three Sisters”. Reaching this number of films in a week has required a lot of dedication, coffee, and unhealthily obsessive behaviour. But it is largely rewarding, and there have been very few lemons in the bunch (my colleague Pia MAY have outed my distaste for the new Terrence Malick movie in a previous article…).

The nice thing about an international film festival is that you can - very safely and environmentally consciously - travel to really just about anywhere with these films. The directors and storytellers behind them take you on a much more intimate journey as well, exposing you to local cultural traditions, laws and lifestyles that you would be unlikely to be exposed to as a tourist.

Whether it is through amazing documentaries (Exhibit A) or realistic fictional depictions of life in different parts of the world (Exhibit B), or even fantastical otherworldly films which still manage to offer a twisted carnival mirror’s reflection of the world we live in today (Exhibit C), this year’s Viennale has taken me on some of my best journeys of the year.

Exhibit A: Documentaries

Let’s begin with the documentaries. One of my personal highlights was 143 Sahara Street (143 Rue du Desert), the new film from Algerian director Hassen Ferhani, which documents the life of an elderly woman named Malika, who runs an incongruous roadside café along the main highway of Algeria’s Sahara Desert. Though she and her wildly diverse base of customers are well aware of the camera filming their every move, they all seem very blasé about it, which lends a real intimacy to the whole affair. They make small-talk about a recent car that went off the road, or the new gas station under construction, family, religion, and infrastructure, and you feel like a fly on the wall, watching it. The setting is totally alien to begin with - and yet, the familiarity of the protagonists makes it almost feel like home by the very end.

Another highlight was the bizarrely wonderful Austro-German documentary Space Dogs. On the surface, the film was about all of the animals that humanity has sent into space as unwilling astronauts (most prominently some stray Muscovite dogs, but also apes and turtles). But more time is actually devoted to following the day-to-day life of a pair of stray dogs living today in Moscow... and that’s where things get really weird. By following these animals around for so long, you find yourself interpreting and anthropologising the ways they act as if they think like humans, which clearly they do not.

The film really serves to question how much we project our own ideas onto animals, and highlights how alien and unknown the lives of these animals really are to us; the more time we spend with „man’s best friend“, the less we seem to understand them. An intriguing and troubling film.

Exhibit B: Fictional Depictions

There are so many good films at the Viennale that play out like documentaries, although they are not. Ghost Tropic, about one night in the life of a headscarf-wearing cleaning lady living and working in Brussels, is a good example. So is Luciérnagas (Fireflies), which documents the day-to-day difficulties of a gay Iranian migrant worker who finds himself inadvertently trapped in a place where he does not speak the language nor understand the local culture, and where job opportunities are few: Veracruz, Mexico. Another powerful example is the Patagonian historical drama Blanco en Blanco, which unflinchingly depicts child marriage, and the genocide of local indigenous peoples, at a time when such things were considered normal and not even blinked at.

Di Jiu Tian Chang (So long, my son) functions as both a critical indictment of China’s one child policy, and a meditation on how families deal with loss, guilt and trauma; the Turkish film Kız kardeşler (A Tale of Three Sisters) depicts the hopelessness and desperation of people living without prospects in a remote village in Central Anatolia; Zombi Child shows us real-world voodoo traditions in Haiti where people are kept as slaves in a half-dead zombified state - a disturbing tradition that provided early inspiration for zombie movies.

Viennale

Moi Dumki Tikhi

However, my personal favorite film so far, in this totally made-up category of realistic films about real things, was the Ukrainian film Moi Dumki Tikhi (My Thoughts Are Silent). The film follows a very awkward young Ukrainian sound designer named Vadym on a trip around the country with his mother, who he doesn’t get along with very well. His job is to record the sounds of Ukrainian wildlife - both common and rare - for a video game company in Canada. The reward for a job well-done is the opportunity to move legally to Canada, and escape from his unsatisfying life in Ukraine.

People who should enjoy this film: Any person who has ever felt like they didn’t belong in the world they grew up in, who is both embarrassed by, and embarrassing to, some of their closest relatives. It’s funny, heartwarming, totally relatable and totally absurd, all in equal measure.

Exhibit C: The Fantastical

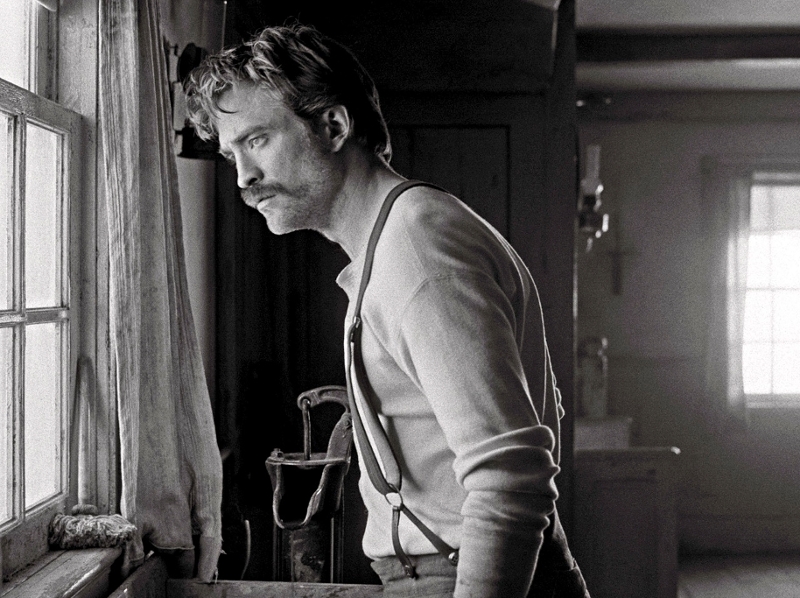

By far the most effective horror trip out of this world that I’ve taken at the Viennale was the new Robert Egger film The Lighthouse, starring Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson as a drunken lighthouse keeper and his young, secretive assistant. Without giving too much away, let me just say that the film throws every disturbing bit of maritime mythology that one can think of into a single film - the world is a fully-realized hallucination of a small island in a stormy sea surrounded by fog; you taste the salt on your lips, and learn to be afraid of siren-like mermaids tempting you to your death. You learn to be superstitious about sea gulls and slight changes in the wind; by the end, you even begin to believe in King Neptune himself. The film is a fantastic escape.

A 24 Films

The Lighthouse

Another film that tempts you to question your reality is an admittedly more humble one: Repertoire des Villes Disparues (Ghost Town Anthology) is the new „horror“ from French-Canadian arthouse director Denis Côté. I put „horror“ in quotations because, while the film plays with fear of what lurks in the shadows, and there are zombies of a sort, they are absolutely non-violent zombies who just stare at you, and the fear of what lurks in the shadows might simply represent a fear of the Other, and a fear of change.

Featuring the kinds of eccentric characters that one recognizes from small towns everywhere, Ghost Town Anthology felt very much like a French-Canadian answer to Twin Peaks, but without trying to be. I’ve seen other films at the Viennale which also seemed to be trying to channel the dark surrealism of David Lynch’s early work (*cough*Knives & Skin*cough*), but fell into the trap of being kind of derivative. Ghost Town Anthology seems like a film that accidentally reminds you of the best parts of Twin Peaks.

On a final note, two of my personal favorites of the fantastic are both technically Brazilian sci-fi. Both of them take place in the very near future - without feeling particularly futuristic. They feel very credible, very much like they could be happening today... Which makes them even more disturbing, as twisted reflections of the world we are living in, or could be living in soon.

The first one is Divino Amor (Divine Love), which puts us on a bridge somewhere between the world we live in today, and the horrors of Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale. The religious government of this future Brazil („the Party of Supreme Love“) judges every couple by if they are able to stay together, and produce offspring - those who can’t, get quietly shunned.

The film is a very well-realized look at the manifold ways a cult-like Evangelical government can impinge on the rights of its citizens. I found it very believable.

Then there’s Bacurau, which takes place only a few years in the future.

A small, off-the-grid community suddenly finds itself literally being erased - the town no longer appears on maps, and the phones suddenly have no signal. Soon gun-wielding militants descend on the town, and the locals have to band together to survive.

Victor Juca Fotografia

The plot of Bacurau is interesting, the pacing is good, and one is constantly at the edge of one’s seat - but that’s actually not even why I have bothered to mention it. I’ve chosen this film (which incidentally won the Cannes Jury Prize) because of how „real“ the people living in the town of Bacurau feel. They live proudly in their own way, with little interaction with the outside world.

The little disputes in the town, the relationships between people and the local politicians, and the whole way that the community interacts - it doesn’t feel like something that was created for a two hour movie. It feels like something that was already there when the director (Kleber Mendonça Filho) turned on his cameras. And therefore, you worry about the fate of the local people so much more, because they absolutely feel like they already exist.

These were some of the most interesting places I’ve traveled to this week!

Publiziert am 02.11.2019